So when I heard that there was a very disgruntled welcome party surrounding his parent’s house, I wasn’t surprised. When a high profile case hits home, our safety can feel threatened and our anger more fueled because this horrible thing that someone did impacts our own community. Our friends and families. Our college students. Our kids. The illusion of our safe little suburb is broken when we realize a rapist lives down the block or around the corner. That he might do here what he did to a woman in California. It’s terrifying.

Our anger about this case—and about sexual violence more broadly—is absolutely justified. But I must admit I'm uncomfortable with the messages armed protesters communicated to Turner and arguably, potential rapists in our region with their signs: things like “Castrate rapists” and “If you try this again, we will shoot you.” These statements advocate a powerful, bold stance against sexual violence, but they also reflect societal perceptions about rape that aren’t necessarily productive for actual, effective prevention and response.

I applaud the fact that people are mad and willing to do something to let other people know that. The outrage of these protestors draws more needed attention to the issue of rape, which is something I believe all of us as a culture should be much angrier about. I also support free speech and acknowledge that it is completely within the rights of these individuals to open-carry and express their perspectives. And yes, Turner should have been held more accountable for his despicable actions.

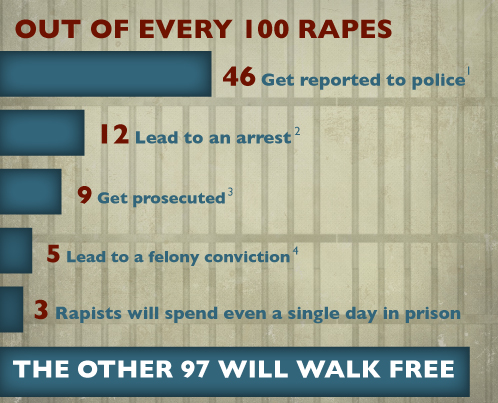

But I also wonder whose interests are best supported with a protest like this. One might argue that justice has already been served (though poorly) because Turner did the time for his crime. Realistically speaking, his case actually represents somewhat of a success of our legal system. Hard to stomach, I know. Our criminal justice system is so incredibly messed up that he is part of the mere 3% of rapists who serve prison time—primarily because so few people report sexual violence, reports aren’t always taken seriously by police, investigations aren’t always thorough, charges don’t often lead to convictions, and convictions may not even result in prison sentences. In this case, the major issues involved loopholes in the law and a judge who did not understand the dynamics of sexual violence. But Turner still served time. It’s not enough, but it is something. Turner benefits from our crappy criminal justice system, but it is not his fault the system sucks. It’s ours.

What would it mean if all of the time and energy spent protesting Turner was redirected into demanding better laws, mandatory education about rape for judges and elected officials, more training for police officers, and forums for discussing the impact of gender violence in our communities and what we can do about it? What if it meant seeking support to create rape crisis centers that can respond to the needs of those impacted by sexual violence and spearhead crucial prevention efforts in our schools and on our college campuses? Dayton does not have a rape crisis center, by the way. Don’t tell Brock.

Unfortunately, we can’t control whether or not this guy rapes again. He probably will: research shows that most dudes who rape do it repeatedly, and Turner fits the bill.

Is castration the answer? No. Another Debbie Downer fact for you: even when castration has been used to treat sex offenders, there has been no evidence that it actually cures anything. This is probably because rape isn’t causes by a disease, the people who commit it aren’t necessarily “sick,” and penises are not the epicenter of some kind of gender violence gene scientists have discovered in people who commit rape. In actuality, our culture produces rapists in the ways that we cling to traditional gender roles that, in their extremes, lead to dangerous expressions of masculinity at the expense of others’ rights to bodily agency and safety. We support rapists when we normalize sexual violence in various forms of media, minimize the daily reality of rape or the threat of it for a huge proportion of our population, victim-blame and slut-shame people who have experienced sexual violence, and refuse to believe that rape is as pervasive and widespread as it is.

For every Turner, there are thousands more rapists out there. I know: I worked at a crisis center for several years and struggled with carrying the detailed knowledge of so many situations—including the names of rapists and who they had attacked and where these things had happened—that I could not share with anyone because of necessary and important confidentiality laws. These things happen everywhere whether we are aware of it or not, and they happen much more often than we realize. Every community does not need a Brock Turner to get enraged about that. But we do need to back up our anger with the time, energy, and resources crucial for transforming our cultural acceptance of rape and supporting individuals who have experienced sexual violence.

The threat of vigilante justice might feel cathartic in the short term, but real change requires a deep investment in comprehensive gender violence prevention and victim-centered services. Forget castrating Brock Turner. Let’s cut out the disgusting parts of our culture that minimize, normalize, and encourage sexual violence. That’s the kind of castration I can get behind.

---

To demand better rape prevention and response efforts in Dayton, OH, contact:

Mayor Nan Whalen

Senator Rob Portman

Senator Sherrod Brown

Representative Michael Turner

RSS Feed

RSS Feed